The birds had perched above the car whether or not they were noticed. But it was noticing them, not their arrival, that made the man worry.

“Risks change over time, but so do investors’ perceptions of those risks.”

Markets are similar. Risks change over time, but so do investors’ perceptions of those risks, and the two feel no particular compunction to stay aligned. When investors are lulled by recent experience into diverting their gaze, they can view the world as more predictable than it is, the range of outcomes too narrow. As their aperture widens, like walking towards a distant window, they become aware of risks they hadn’t previously considered. Then comes fear, and the trading that pushes that fear into market prices.

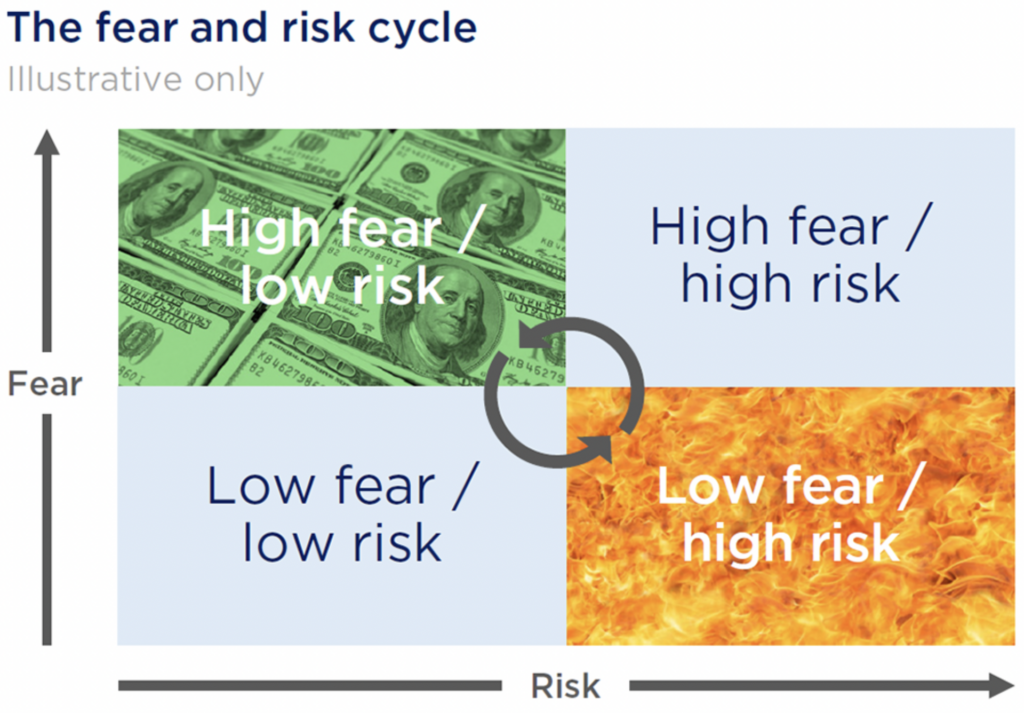

We call this the fear and risk cycle. Much of the time, the market’s fear level is about right, and prices roughly reflect risks. Occasionally, actual risks are receding, but fear remains high—those are the best buying opportunities for contrarians, because investor fear keeps prices undeservedly cheap. And sometimes, risks are rising, but fear remains low. Those are the most dangerous periods.

“In our view, this environment calls for a bit of humility. That boils down to two things: get actually diversified, and hold cheap stuff.”

Coming into this year, we believed we were in the bottom-right quadrant. As we looked around the world, we saw a rising number of real-world risks, yet the market was untroubled, so many assets traded at shockingly high valuations. Fear was low but risks were rising. This year, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, pervasive inflation, and ever-tougher talk from the Federal Reserve, the market’s perception of risk has risen, and prices have fallen.

That does not mean the risks have gone away, and valuations have moved less than it seems on first glance. True, the MSCI World Index is down nearly 20% since the start of the year, and now trades at a lower price multiple. But all of that decline is arguably explained by rising bond yields. Compared to bonds, global equities are actually more expensive now than they were at the start of the year.

In our view, this environment calls for a bit of humility. That boils down to two things: get actually diversified, and hold cheap stuff.

Getting actually diversified does not mean matching the risks of a passive index whose shape has been moulded by others’ greed and fear. Should the next ten years look like the last ten, the World Index should be fine. But we believe it is woefully unsuited for a world of even moderately higher inflation and interest rates.

We prefer to own shares that can work in a range of possible environments, because we’re not sure which future we will get. So we own some companies, like discount retailers and managed health care organisations, that should hold up well in a typical deflationary recession. High-quality companies like Alphabet, which we discussed last month, can benefit from falling bond yields. Others, like banks, should thrive if growth recovers and yields rise. And several, like energy and metals companies, should provide balance if countries continue to suffer from both high inflation and recessions. Importantly, we believe the shares we own are cheap compared to their intrinsic value.

“With each passing year, your need for a crystal ball dissipates, because the companies generate so much cash.”

Owning cheap stocks can also be an expression of humility. If you were convinced you knew the future, you would be prepared to pay vastly different prices for companies, and sky-high valuations for those you knew would grow fastest. If you were convinced the future was unguessable, you would simply buy the cheapest cash flows you could find. With each passing year, your need for a crystal ball dissipates, because the companies generate so much cash.

We are pleased, then, that the gap in valuations between cheap and expensive stocks remains so wide, and the Orbis Global Equity Strategy continues to have an unusually strong exposure to “value” stocks trading at low price multiples.

So far this year, owning cheap companies has been helpful. While richly-priced “growth” stocks are down more than 20%, value shares are down less than 10%. And interestingly, the relative performance of value shares has been negatively correlated with the overall direction of the stockmarket. That isn’t typically the case—in fact, the last time the correlation was this negative was in 2000, when the tech bubble burst.

Sometimes it pays to be humble.

This report does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any interests, shares or other securities in the companies mentioned in it nor does it constitute financial advice.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of investments in the Orbis Funds may fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you originally invested. It is therefore important that you understand the risks involved before investing. This report represents Orbis’ view at a point in time and provides reasoning or rationale on why we bought or sold a particular security for the Orbis Funds. We may take the opposite view/position from that stated in this report. This is because our view may change as facts or circumstances change. This report constitutes general advice only and not personal financial product, tax, legal, or investment advice, and does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or individual needs of any particular person. This report does not prohibit the Orbis Funds from dealing in the securities before or after the report is published.